L.A. Law: The Computer Game might not be the worst computer game I’ve ever played, but it’s certainly the one that’s felt the most like work.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying this is a great game by any stretch of the imagination. And the jury’s still out (pun not intended) as to whether or not it’s an objectively good one. But man, L.A. Law embodies one of my least-favorite adventure-game design choices, if this can even be called an “adventure game”: trial and error.

And believe me, this pun was also not intended.

Let’s pick up this thread for a second though. Adventure games usually consist of things like inventory based puzzles, exploration, and an overarching story. L.A. Law has none of these things. Maybe it has an overarching story if you look at the career dreams of your player character of choice. But in general, this game seems pretty thin in the adventure game department. Still, my torture is your entertainment, so without further ado, recess is over and court is now in session!

Okay, these puns were intentional. And I’ll show myself to the door now . . .

The Case

We left off with Victor Sifuentes, fresh off of his loss in the Rextor Avionics case, being assigned to defend Anthony Hamilton, a man accused by Child Protective Services of beating his five-year-old son Jeffrey.

This is a horrible allegation, and Mr. Hamilton isn’t exactly a sympathetic defendant. But as Victor’s colleagues say during their morning meeting, isn’t everyone deserving of the best legal defense possible? And what if . . . what if Mr. Hamilton is innocent?

Will I be able to find evidence exonerating my client and get an acquittal? Or will I at least be able to poke enough holes in the prosecution’s case to at least create reasonable doubt in the minds of the jury? (Remember: this is a criminal case, so the State’s burden of proof is “beyond a reasonable doubt,” i.e., somewhere in the “we’re 90 percent sure he did it” realm.)

Most importantly, will the seven in-game hours given to me be enough to mount a proper legal defense?

Trial Prep

The case notes provide a pretty solid rundown of who I should contact, most of the pretty obvious. First, you always want to talk to your client to get their side of the story. Next, you want to talk to witnesses both for and against your client to see (1) what evidence the prosecution has and (2) what you can do to refute this evidence, either via counterevidence or otherwise calling the credibility of the prosecution’s witnesses and evidence into question.

You know, fun lawyer stuff. I mean “fun.”

I start by calling Child Protective Services (CPS). They’re convinced that my client is a child-abuser, and agree to send me the medical report. They also inform me that all they need to prove that a child should be removed from a home is “reasonable belief” that the child is in danger. Note that this says nothing about from whom the child is in danger from.

Next, I call the defendant’s wife Nancy. Much to my surprise, she agrees to come to Victor’s office. Or she mails a cardboard cutout of herself and just stays on the phone. Either way, I start to question her . . .

. . . but for whatever reason, the game sends her home after my first round of questions. What happened here? All I got out of her before she decided to split was that she never actually saw her husband hit Jeffrey. I sure would’ve liked to have asked her more questions, maybe discovered if there was someone else I should talk to, but whatever. The game had had other ideas. As commenter Lugh stated in the last post, “Capstone should have been put on trial for their crimes against entertainment.”

Undaunted, I move on and call my client who, along with his bitchin’ ponytail, stops by the office to answer a few of my questions.

I’m sorry, but the professional in me can’t stop laughing at the absurdity of this situation: With the trial mere hours away, an attorney is just now meeting his client. The guy could potentially go to jail for something he might not have even done, and we’re just beginning to build our defense seven hours before show time. It’s all so stupid. It’s not like we’re the public defender, meeting our indigent clients in the courtroom. We were hired by the guy to do a job and are acting with extreme negligence and, dare I say it, incompetence.

And then I remember that I really should just relax because it’s just a game.

Back to Anthony Hamilton. He has some interesting points to make:

- He and his wife think that Jeffrey is accident-prone: he’s always coming home with bruises and scrapes just like Mr. Hamilton here did when he was a boy.

- He thinks his wife is slightly over-protective of Jeffrey, but doesn’t seem angry about it.

- He vehemently denies ever beating Jeffrey.

- He claims to have been either in the garage working on his wife’s car or elsewhere fixing something when these incidents occur. This sparks me to think that maybe I can prove Hamilton was nowhere around when he is alleged to have beaten his son.

The medical report, which magically appeared in Victor’s file, notes four separate incidents of alleged abuse. Poor Jeffrey’s injuries also seem odd . . . bruises I can see, but lacerations? Is he being cut or scratched?

With trial looming near and no one else to call, I decide to visit the District Attorney’s office. And there she is, sitting in the same office that Mr. Forentello’s lawyer from the last case was sitting in.

I learn that the D.A.’s name is Zoe Clemmons, and she’s very unhelpful. She states that there’s video evidence of Jeffrey testifying that his father beat him, and taunts Victor that he’ll never see it. Now, Victor could submit a written discovery request and be allowed by the laws of civil procedure to see the video tape . . . but nah. I guess he’ll just have to wait and see it in court!

Slightly stymied, I check with my colleagues. My man Mullaney is useful, once again, as is my homie Arnie Becker.

Mullaney’s thought process is in line with my own. I can’t say I agree with Becker . . . the wife didn’t strike me as duplicitous or anything, and a divorce hadn’t come up at all.

Grace Van Owen tells me that she thinks child abusers deserve to rot in jail. Now, I agree with this, but it’s not exactly helpful legal advice. It’s only when Leland McKenzie tells me that Grace will help lay out the prosecution’s likely case that Grace offers any practice tips.

|

| Now that’s more like it. |

Nothing I don’t know, except that I have no idea how to talk to young Jeffrey before trial!

I call private detective Joe Spanoza to see if he can help. And . . . wow! I’m able to ask him about everyone, including the woman who worked at CPS, the doctor, Hamilton’s entire family, including his older son Tony Jr., as well as each of the four dates of abuse! Maybe my client wasn’t there!

I furiously ask Joe to take a look into these four dates, as well as into Jeffrey, Nancy, and Tony, Jr., but quickly run out of time.

|

| Wait, what?! |

I’m pissed at this point. I hate this trial-and-error mechanic. It is very unfair and, to me, indicative of poor design. You can get away with this in an actual adventure game which, as we’ve established, L.A. Law really isn’t—who can forget, say, the mapping puzzles in Leisure Suit Larry 3 or Space Quest V (as much as we wish we could)? Here, given the limited time-frame and no clue as to whether the options presented are useful or are red herrings, it all just seems unfair.

Anyway, I reload and call up Nancy Hamilton, determined to actually get a chance to speak with her. The game lets me this time and I learn a few more facts, nothing totally dispositive, but useful nonetheless:

- She can’t remember her husband getting angry at Jeffrey.

- Her husband used to have anger issues when he was an alcoholic, but he’s been sober for several years now.

- While an alcoholic, their elder son’s misbehavior frequently caused Anthony to lash out at the boy; “no beatings,” by her own admission, but Anthony did “spank him pretty hard.”

- She never saw Anthony beat Jeffrey, as Nancy claims she was always busy with something when the incidents occurred.

- Tony, Jr. plays with older boys from his sports teams. They don’t come by the house much.

- Jeffrey goes to a pre-school.

But guess what: I still run out of time before I can get Joe’s reports back about anything. This is maddening, but I’m not going to try this investigation a third time. And anyway, the D.A.’s case seems pretty weak: Jeffrey told the doctor he “fell down”—I know, I know, the classic excuse—but changed his story on video. And . . . that’s really it. Presumably, she’ll call this Dr. Nelson, too. I doubt she’ll call Nancy Hamilton, since her testimony, if anything, seems to play into Anthony’s favor. Lastly, she’ll likely call Jeffry.

Okay, now that I’ve rendered my expert legal analysis, I actually feel pretty good about this one. Let’s poke some holes in the D.A.’s case! Remember: we’re trying to establish that Anthony Hamilton was not around Jeffrey when these alleged beatings occurred. Let’s do this thing!

The Trial

|

| It’s on! |

The D.A. starts by alleging that Jeffrey and Dr. Nelson will testify that Anthony beat Jeffrey on at least four occasions and that Anthony is guilty!

Come on, look at that face! Does this man look guilty?

Actually . . . I kind of wish this game had the budget (or the wherewithal) to make your character’s clients show up to court in a damn suit! Defense Lawyering 101—ALWAYS MAKE YOUR CLIENT LOOK AS RESPECTABLE AND SYMPATHETIC AS HUMANLY POSSIBLE! It’s a small thing, but these psychological tricks work.

Anyway, Victor lets loose with what I think is the strongest of the three available opening statement strategies (which I didn’t get any screenshots of): that Anthony Hamilton was nowhere near Jeffrey when the alleged beatings occur.

The prosecution begins by calling Dr. Nelson to the stand. After the basic introductory questions, necessary to establish who a witness is and why they should be found credible, the D.A. asks him to discuss what he thought happened.

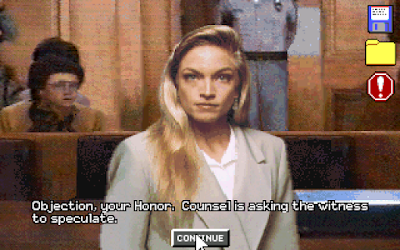

My red flags go up.

|

| I like this judge. |

The D.A. rephrases, and merely asks Dr. Nelson to describe the injuries. This is her final question.

On cross, I begin by asking the doctor how he thinks Jeffrey got the bruises:

|

| Yep. I like this judge. |

I get Dr. Nelson to admit that he has no idea how Jeffrey got these bruises, and that Jeffrey never told him his father had hit him.

Damn, son!

The D.A. then calls Jeffrey Hamilton to the stand. The Judge warns her to be careful. See, there are always issues with child witnesses, as they are very open to the suggestion of adults. Which makes sense, since little kids are dependent on adults for everything, and believe adults have authority and always act in their best interests . . . which they quickly grow out of thinking during their teenage years, but I digress. More importantly, children want to please adults, and will often say what they think the adult wants to hear.

It’s all very terrible. Kids in courtrooms make me sad.

Anyway, take a look at this picture: There’s no way the actor portraying Jeffrey here is five.

|

| Uh, no. |

I object to every damn question, and even request a recess when I think the D.A. goes over the line by practically begging Jeffrey to tell her that her dad beat her, but I get nowhere. Strangely, Jeffrey says that his brother will know who hurt him.

Anyway, on cross, I get Jeffrey to testify that he likes to ride his bike and climb trees, and that he likes to play with his older brother, but that his brother doesn’t like Jeffrey tagging along.

The prosecution has no more witnesses, so Victor kicks things off McKenzie, Brackman-style by calling Nancy Hamilton to the stand.

I get her to talk more about Tony Jr., starting to get the idea that maybe the older brother is beating poor Jeffrey.

|

| I still like this judge. |

Nancy testifies that, come to think of it, Jeffrey was playing with Tony Jr. when he’d been hurt. I also get her to admit that she never witnessed any injury to Jeffrey based on the deposition I took where she stated as such.

Wait, deposition?!

Hold up now. I never deposed Nancy Hamilton. I had her come to Victor’s office for an off-the-record interview. A deposition is carried out on the record, being recorded by a stenographer. This is why it’s admissible in court as though the deponent was actually there.

Anyway, I’m just going to roll with this.

I also get Nancy to testify that Anthony travels a lot for work . . . the first full week of each month. Hmm . . . July 9, 1992 was one of the alleged dates of injury. Looking at my computer’s calendar, it turns out that July 9, 1992 was the first full week of July that year. Maybe this is the opening I need to create some reasonable doubt. It sure would’ve been nice to have known about Mr. Hamilton’s travel schedule prior to trial, but oh well.

The upshot is that I introduce the possibilities that Tony Jr. hurt Jeffrey, and that, for at least one of these incidents, Anthony was not present.

I decide not to ask about Anthony’s alcoholism. Sure, there’s a tactical advantage in bringing something up before the other side does, but here I’m afraid that opening the door, essentially doing my opponent’s job for her, would do more harm than good.

Supposing this game is programmed to take advantage of this.

Amazingly, the D.A. doesn’t cross-examine Mrs. Hamilton . . .

I call Tony Jr. to the stand next. He looks pretty gnarly.

|

| Think I went to high school with this dude . . . |

Over the D.A.’s objections, I ask Tony Jr. why Jeffrey would state that he knows how Jeffrey got hurt. He also testifies, over the D.A.’s increasingly more futile objections that:

- He’s hit Jeffrey.

- It’s normal to hit Jeffrey because they’re brothers.

- He’s hit Jeffrey hard enough to cause bruises.

- He hits Jeffrey because he doesn’t want Jeffrey to be a sissy the way that Anthony used to always talk about toughening up Tony Jr. when he was younger.

I object, and Judge McAwesome is pretty pissed at the D.A.:

Riding high, I call Anthony himself to the stand and get him to establish his travel schedule, as well as the fact that he wasn’t around Jeffrey when the alleged beatings occurred.

|

| Suck on that, Zoe! |

The judge asks the parties to approach the bench, stating that she’s inclined to grant the defense summary judgment.

I think she means a directed verdict, which is an instruction to the jury to find a certain way, given that no reasonable jury could find otherwise based upon the evidence presented.

Yeah, I know that’s squishy and ambiguous. Welcome to the practice of law.

Summary judgment is a motion that’s filed before trial—you know, with motions deadlines and stuff—essentially telling the court that no material facts are in dispute and that the other side can’t refute the evidence, so why have a trial? Just give me judgment as a matter of law. The other side then has to introduce disputed facts, via a written response, or lose. This doesn’t happen at trial, as far as I know.

But whatever. A minor quibble. In the trial menu, I can also ask for a directed verdict, which I arguably should have done here, but instead I let the D.A. question Anthony Hamilton, as is her right . . . and she immediately gets into his alcoholism.

|

| I don’t know if I like this judge anymore. |

The D.A. tries to paint Anthony as a child-beating drunk, still in the thrall of that demon alcohol. She berates and cajoles him over most of my objections, but the judge does sustain a couple. Unfortunately, Anthony admits to hitting Tony Jr. and “disciplining” Jeffrey, though nothing bad.

Here’s the funny thing about objections though: sometimes just asking the question that gets objected to is enough, despite the judge’s instruction to the jury to ignore the question. Right. Like you can just rewind life as though it were a computer game! If I could hit “Restore!” during some real-life trials, their outcome sure would’ve been a lot different . . .

But in the end, it doesn’t matter, since the judge doesn’t even send this to the jury—she dismisses all charges against Anthony!

|

| Woo! |

Now, maybe this was a bench trial case—a case where the judge is both the finder of law and fact—as opposed to a jury trial case—where the judge is the finder of law and the jury is the finder of fact. I don’t know; I’m not up on early-1990s California child abuse laws. In any event, the Judge also sends Tony Jr. to juvenile detention, requests regular progress reports, et cetera. The important thing is that Victor Sifuentes helped an innocent man beat some pretty devastating charges against him!

All right! Now that’s how you bounce back, baby! Sure, it helped that the D.A. had a pretty awful case and introduced no real evidence showing that Anthony Hamilton beat Jeffrey. I’m happily putting this into the “win” column and moving on to the next one!

Session Time: 40 minutes

Total Play Time: 2 hours, 30 minutes

Record: 2-1

So, is it just up to judge to say when witness is considered to speculate and when not? Is there no possibility to complain, if the judge appears to favour one side?

ReplyDeleteComplain about a judge? In court? And have it do anything other than get the judge mad and perhaps hold you in contempt, which can result in fines and potentially jail time? Never.

ReplyDeleteOh, you CAN lodge an official complaint against judges, but they do no good. It’s a REAL high bar to prove bias.

Generally, the attorney has to state the grounds of an objection, and the judge makes the call; if I remember it’s not always a hard-and-fast rule. A lot of balancing (harm to one side vs. the other, enduring the jury gets the full story vs. potentially unfairly biasing the jury, the actual probity of the testimony, etc.)

The main reason to object against things is so the objection is on the record, and can layer be appealed. For many thing, no objection on the record, no possibility of appealing.

Objecting can also throw the other side off their game...but judges will get mad if an attorney pushes it too far.

Broken Sword 5 and Tesla Effect for $1? Sounds like a good deal to me.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.humblebundle.com/games/classics-return-bundle

Just going through these posts now. I'm enjoying them.

ReplyDeleteProbably because solving / unraveling mysteries is compelling stuff, and it translates well to blog posts. Better than, say: "I killed an orc. Then another. And then three orcs! So many gold pieces."

Your legal background enables some good commentary on what is or isn't realistic... this makes it more enjoyable to read about the game.

I'm sure this is a case of a game that's much more fun to read about (or watch someone else tinker with) than to actually play.